Tactical Investing to Help Protect and Grow Your Portfolio

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Investment Management

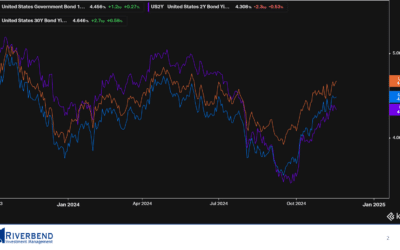

Using our proprietary investment methodology, our portfolios are actively managed to adapt to the ever-changing stock market and economy.

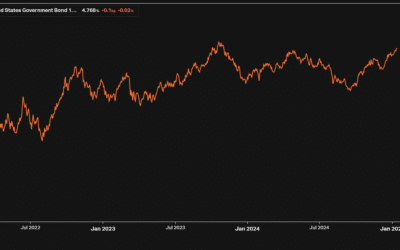

Risk Management

All of our portfolios have a risk management overlay to help reduce downside risk and volatility during market declines.

Fee-Only Fiduciary

Founded in 2006, Riverbend Investment Management is a Registered Investment Advisor (RIA) and acts in a fiduciary capacity with all our clients.

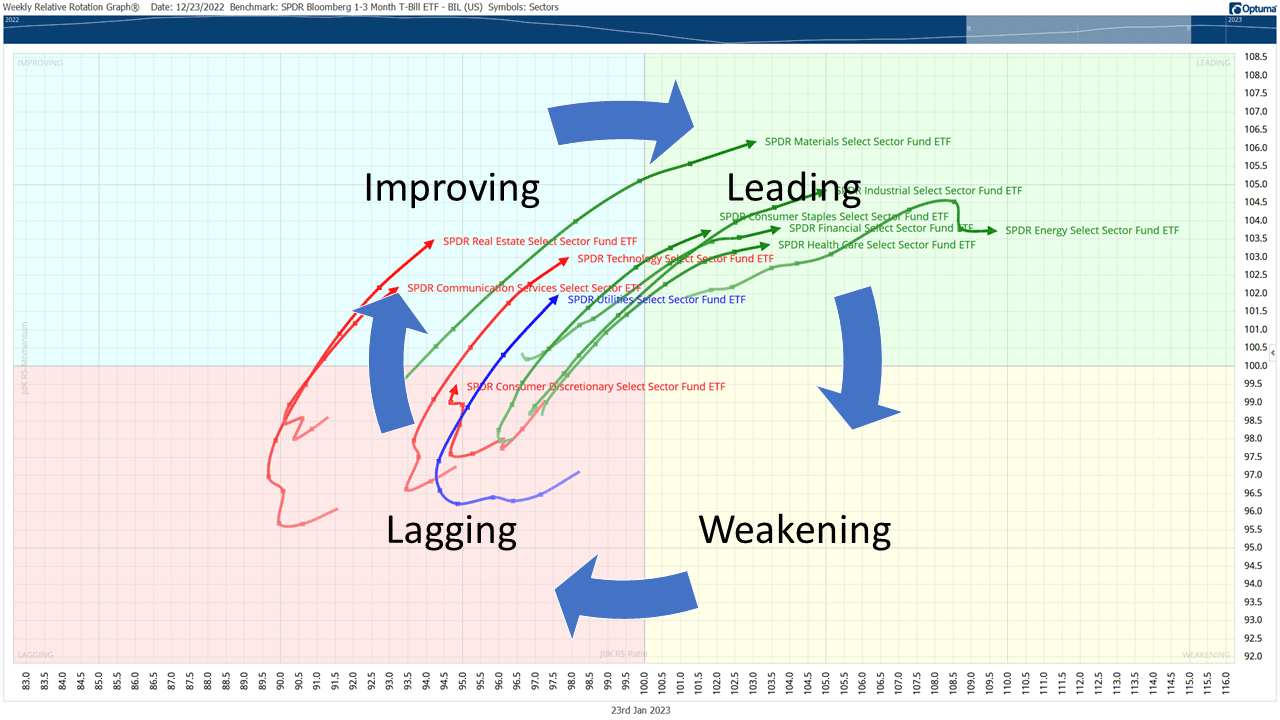

Advanced investment modeling tools help guide our portfolios into the strongest growth opportunities within the stock market.

Let Us Help You Build a Secure Financial Future

Latest Updates

As featured in